He argues that the attack on Pearl Harbor provoked a rage bordering on the genocidal among Americans. Letters and diaries written by student conscripts before they were killed in action speak of harsh beatings, and of soldiers being kicked senseless for the most trivial of matters - such as serving their superior's rice too slowly, or using a vest as a towel.īut John Dower, one of America's most highly respected historians of wartime and post-war Japan, believes a major factor, often overlooked in seeking to explain why Japanese soldiers did not surrender, is that countless thousands of Japanese perished because they saw no alternative. What in some cases inspired - and in others, coerced - Japanese men in the prime of their youth to act in such a way was a complex mixture of the times they lived in, Japan's ancient warrior tradition, societal pressure, economic necessity, and sheer desperation.Īpart from the dangers of battle, life in the Japanese army was brutal. Even today, the word 'kamikaze' evokes among Japan's former enemies visions of crazed, mindless destruction. The other enduring image of total sacrifice is that of the kamikaze pilot, ploughing his plane packed with high explosives into an enemy warship. Not only were there virtually no survivors of the 30,000 strong Japanese garrison on Saipan, two out of every three civilians - some 22,000 in all - also died. To the horror of American troops advancing on Saipan, they saw mothers clutching their babies hurling themselves over the cliffs rather than be taken prisoner. In the last, desperate months of the war, this image was also applied to Japanese civilians.

From figures of derision, they were turned into supermen - an image that was to endure and harden as the intensity and savagery of fighting increased.Īlthough some Japanese were taken prisoner, most fought until they were killed or committed suicide. The speed and ease with which the Japanese sank the British warships, the Repulse and the Prince of Wales, off Singapore just two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor - followed by the humiliating capture of Singapore and Hong Kong - transformed their image overnight. Since Japan was having such difficulties in China, the reasoning went, its armed forces would be no match for the British. This gross underestimation can in part be explained by the fact that Japan had become interminably bogged down by its undeclared war against China since 1931. In early 1941, General Robert Brooke-Popham, Commander-in-Chief of British forces in the Far East, reported that one of his battalion commanders had lamented, 'Don't you think (our men) are worthy of some better enemy than the Japanese?'

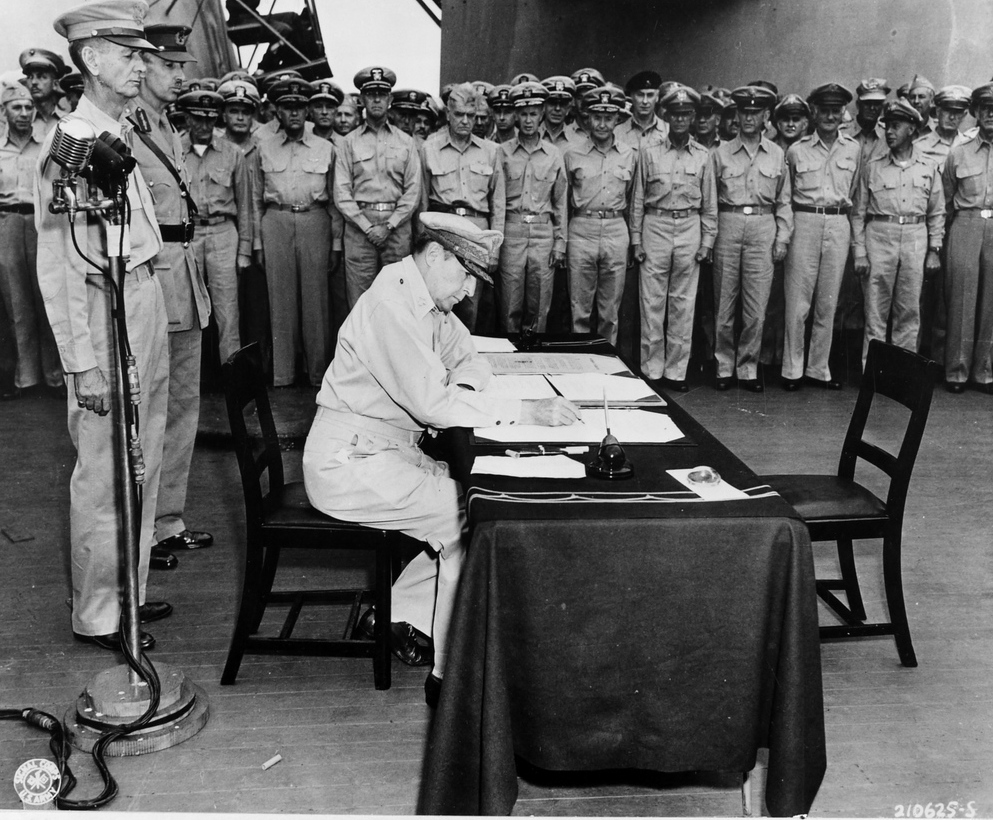

But the most extraordinary story belongs to Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda, who continued fighting on the Philippine island of Lubang until 9 March 1974 - nearly 29 years after the end of the war.īefore hostilities with the Allies broke out, most British and American military experts held a completely different view, regarding the Japanese army with deep contempt. Other, smaller groups continued fighting on Guadalcanal, Peleliu and in various parts of the Philippines right up to 1948. Tens of thousands of Japanese soldiers remained in China, either caught in no-man's land between the Communists and Nationalists or fighting for one side or the other. Yet not everybody was to lay down their arms. To most Japanese - not to mention those who had suffered at their hands during the war - the end of hostilities came as blessed relief. Nearly three million Japanese were dead, many more wounded or seriously ill, and the country lay in ruins. It was a classic piece of understatement. He never spoke explicitly about 'surrender' or 'defeat', but simply remarked that the war 'did not turn in Japan's favour'. When Emperor Hirohito made his first ever broadcast to the Japanese people on 15 August 1945, and enjoined his subjects 'to endure the unendurable and bear the unbearable', he brought to an end a state of war - both declared and undeclared - that had wracked his country for 14 years.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)